Well, anyone who knows me at all well knows that the first book on my fiction shelves is going to be Middlemarch. If I could download it direct into your heart and head, I would do so, no qualms, no questions, no quibbles listened to. I was delighted to discover, listening to Point of View a few Sundays ago, that I share Middlemarch madness with Howard Jacobsen, who apparently can’t stop himself raving about its life-enhancing capacities, even during launch events for his own books. His agent watches—chagrined, unsurprised and helpless—from the wings…

Well, anyone who knows me at all well knows that the first book on my fiction shelves is going to be Middlemarch. If I could download it direct into your heart and head, I would do so, no qualms, no questions, no quibbles listened to. I was delighted to discover, listening to Point of View a few Sundays ago, that I share Middlemarch madness with Howard Jacobsen, who apparently can’t stop himself raving about its life-enhancing capacities, even during launch events for his own books. His agent watches—chagrined, unsurprised and helpless—from the wings…

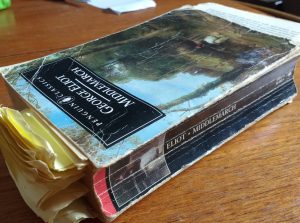

You can see the state of my copy. It’s been with me for nearly 30 years now, and would be my desert island book. It is inexhaustably empathic, wise, honest, brave, inspired, inspiring and visionary; it’s also extremely funny at times, when characters’ pretensions and foibles are quietly, devastatingly exposed. It’s full of ideas, full of head as well as heart, and full of the nineteenth century’s grapplings with the doubts and changes consequent on contemporary developments in science and industrialisation. It’s—well. It’s just the greatest novel I know. It is a long read, and does ask a lot of you. But if you can give yourself a bit of a run-up at it, setting aside time to get a good few chapters under your belt during your first sitting, I reckon it will have you.

Even the teeny-print paperback Penguin is 896 pages long, so I’m not going to attempt any kind of summary here (no doubt the Lords of Wikipedia can give you some kind of précis); and anyway, that’s not really the point. It’s not just the what of the novel that matters, it’s also the how. All the many characters we meet are drawn with such insight, empathy and kindness, and yet also with honesty; all their lives are shown to be interwoven, so that they affect each other in so many different ways, of which they are more and less aware. And each individual self is seen at once from the inside—what the narrator calls their ‘centre of self’—and also from the outside, too, so that the reader is never allowed simply to sympathise nor to judge. We are obliged, somehow, in the course of the reading, to extend ourselves: to become more clear-sighted yet also more compassionate than we thought we could be. The narrator tells us at one point: ‘if we had a keen vision and feeling of ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence’. Middlemarch lets us hear something of that ‘roar’, reminding us that behind every pair of eyes is another story, both different from and similar to our own. And in so doing, it helps us outgrow what Eliot calls our ‘moral stupidity’.

Eliot lost her own formal religious faith in her early adulthood. In the Foreword, she alludes to St Theresa, describing how the saint’s spirit ‘soared after some illimitable satisfaction, some object which would never justify weariness, which would reconcile self-despair with the rapturous consciousness of life beyond self’. Eliot asks how, absent a faith, we can find meaning in this inconsistent, incoherent world. This is scarcely a question we in the 21st century can congratulate ourselves on having solved; but by the end of the novel (and these are its closing words) we have been brought to a place which hears the ‘roar’ and yet can still sustain this hopeful vision:

‘For the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.’

We all matter. If you need reminding of that, or convincing, read Middlemarch.