“Going and looking at stuff” wasn’t always that appealing.

I’m sure I was a disappointingly unresponsive child at times, failing to appreciate carefully-orchestrated opportunities and prone to Dinosaur Rubber Syndrome. For me the formative gift shop experience was at Prinknash Abbey, on a family holiday in That Summer of ‘76. I bought a set of 5 collapsible, flower-decorated biros—unusual colours, and in their own dinky see-through case which closed with a satisfying click. I can still see them; no idea what the Abbey was like… These days, A Nice Potter round something or other—or a longer-distance, more effortful Mission-to-View—is one of life’s small-but-large joys, even better alongside a loved companion with whom I can share or be silent. So I want to celebrate going and looking at stuff.

I’m sure I was a disappointingly unresponsive child at times, failing to appreciate carefully-orchestrated opportunities and prone to Dinosaur Rubber Syndrome. For me the formative gift shop experience was at Prinknash Abbey, on a family holiday in That Summer of ‘76. I bought a set of 5 collapsible, flower-decorated biros—unusual colours, and in their own dinky see-through case which closed with a satisfying click. I can still see them; no idea what the Abbey was like… These days, A Nice Potter round something or other—or a longer-distance, more effortful Mission-to-View—is one of life’s small-but-large joys, even better alongside a loved companion with whom I can share or be silent. So I want to celebrate going and looking at stuff.

The stuff in question for thing 6 is paintings. Some years ago (jings, just seen the date in the catalogue. That can’t be right!) I went to an exhibition of Stanley Spencer’s work, which featured two self-portraits. There was the early and well-known one (1914; see it here)—larger than life-size, and full of the vigour and long view which youth allows. Last in the exhibition was his final self-portrait (1959; here), painted when he knew he was dying of cancer. To move in the space of a half-hour or so from one to the other was a profoundly moving experience: such a telescoping of a life. It was the first time a painting had reached into the core of me without my consent or intention, and wrung my heart, connecting me with the simultaneous agony and wonder of being human. Harrowing, hallowing: the two Hs. Music and poetry had often done it: now the visual arts joined in.

I’d been looking forward to the Caravaggio exhibition for months. Now at last I was on the train to Edinburgh with my mum; a noisy carriage: families and children, classic I’m on the train now, hen, just left Lochgelly phone calls, a couple drinking strawberry daquiris squirted from a plastic pouch. Crossing the Forth we saw the new bridge, whose fanned lines reminded me of those nail-and-string pictures from the 70s; then a slow rocking rumble into town and the final slide into Waverley, easing in along the base of the Castle’s hill. This was time-travel for me—30-odd years since I first went from here down to Cambridge, with everything ahead of me—and left me in a melancholy mood, unready for the crowd and clamour of Princes Street. Then at the gallery an 18-year-old assistant with a nascent beard asked me to wear my backpack on my front (aargh! no concept that, to a peri-menopausal woman, flush+pack=double claustrophia). The stuff had better be good.

I’d been looking forward to the Caravaggio exhibition for months. Now at last I was on the train to Edinburgh with my mum; a noisy carriage: families and children, classic I’m on the train now, hen, just left Lochgelly phone calls, a couple drinking strawberry daquiris squirted from a plastic pouch. Crossing the Forth we saw the new bridge, whose fanned lines reminded me of those nail-and-string pictures from the 70s; then a slow rocking rumble into town and the final slide into Waverley, easing in along the base of the Castle’s hill. This was time-travel for me—30-odd years since I first went from here down to Cambridge, with everything ahead of me—and left me in a melancholy mood, unready for the crowd and clamour of Princes Street. Then at the gallery an 18-year-old assistant with a nascent beard asked me to wear my backpack on my front (aargh! no concept that, to a peri-menopausal woman, flush+pack=double claustrophia). The stuff had better be good.

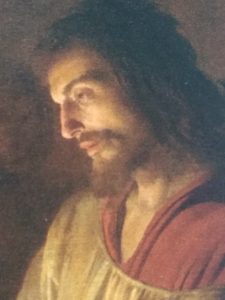

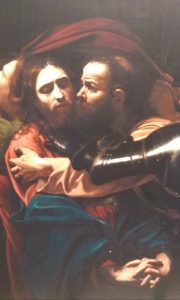

And of course it was. There was a wide range of Caravaggesque works, and it was great to see them, and to understand more about his influence. I delighted, too, in having another chance to marvel at ‘The ‘Supper at Emmaus’ (here)—how it captures that specific moment of utter shock before the wonder of what-this-means has had time to kick in. But for me, the exhibition was mostly about two paintings: van Honthorst’s ‘Christ Before the High Priest’ (here) and Caravaggio’s ‘The Taking of Christ’ (here).

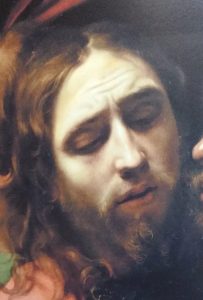

The van Honthurst is huge, with much of the canvas empty. The single light source is a candle on the table, where sits the priest, addressing Christ, the prisoner. It is the middle of the night. The false witnesses—arms folded, satisfied-looking—are to the left of the priest; to Christ’s right, but also in the background, soldiers and others stand, spears planted, intent on what is happening, one craning round from behind another to see. Like any other bureaucrat, now or then, the priest is buttressed by table, books, stuff (I thought of the plastic screens at the council office where I go, subject, to talk about my housing benefit claim); Christ, made to stand while the other sits, is silently resolute, accepting, and unutterably sad. By contrast ‘The Taking of Christ’ is active and violent. Figures are crammed, jostling right to the front of the oppressively crowded image. On the right a rubbernecker (a Caravaggio self-portrait) lifts a lantern the better to see what’s going on; to the left, John is fleeing, and a soldier grasps his trailing cloak. Other soldiers are

The van Honthurst is huge, with much of the canvas empty. The single light source is a candle on the table, where sits the priest, addressing Christ, the prisoner. It is the middle of the night. The false witnesses—arms folded, satisfied-looking—are to the left of the priest; to Christ’s right, but also in the background, soldiers and others stand, spears planted, intent on what is happening, one craning round from behind another to see. Like any other bureaucrat, now or then, the priest is buttressed by table, books, stuff (I thought of the plastic screens at the council office where I go, subject, to talk about my housing benefit claim); Christ, made to stand while the other sits, is silently resolute, accepting, and unutterably sad. By contrast ‘The Taking of Christ’ is active and violent. Figures are crammed, jostling right to the front of the oppressively crowded image. On the right a rubbernecker (a Caravaggio self-portrait) lifts a lantern the better to see what’s going on; to the left, John is fleeing, and a soldier grasps his trailing cloak. Other soldiers are  powering-in to lay hands on Christ, already clasped by Judas who—yes, of course—is looking past his friend, unable to meet his eyes as he closes in to give the momentous kiss. In the middle of the hubbub, the still figure of Christ leans away from this exquisitely agonising experience of betrayal, showing in all of him—posture, expression, clasped hands—the sorrow and tension of this moment, the effort of willing himself to endure what he has chosen to accept. This is an extraordinary picture.

powering-in to lay hands on Christ, already clasped by Judas who—yes, of course—is looking past his friend, unable to meet his eyes as he closes in to give the momentous kiss. In the middle of the hubbub, the still figure of Christ leans away from this exquisitely agonising experience of betrayal, showing in all of him—posture, expression, clasped hands—the sorrow and tension of this moment, the effort of willing himself to endure what he has chosen to accept. This is an extraordinary picture.

Apparently Caravaggio shocked the establishment by populating his religious canvases with man-on-the-street models. These look like people you’d see in town. Saints are shown to have dusty feet. This is perhaps what the catalogue refers to as his ‘almost brutal naturalism’; from my state of not-very-informed-ness I can only report on what the paintings showed me—which was exquisitely-observed renderings of human experience. Look, they said, look: this is what being human looks like: for frustrated bureaucrat, self-righteous, slightly vengeful witness, curious soldier, gawping onlooker, frightened (and later self-reproaching) friend who runs away, angry friend who gives you away… such a range of human emotion laid bare on canvas. And of course, they show what sorrow, endurance, acceptance and sacrifice look like—loss willingly born, and chosen out of love.

‘Art is the nearest thing to life,’ George Eliot wrote, ‘a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow-men beyond the bounds of our personal lot.’ This is what these paintings did for me: they amplified experience, bearing witness to just how hard it is to be human.* And in their depiction of Christ they made visible the lived experience of setting self aside—what CS Lewis calls the ‘overleap[ing of] the massive wall of our selfhood’. It’s something we all have to do, in great ways and small, in the course of relationships, and can mean anything from mild irritation to daily tolerance to great peaks of agony. There’s something so precious about having this acknowledged, because it returns us to a fuller appreciation of the wonder and mystery of love—of the fact that we do love, and struggle, and hurt, and fail, and succeed. Whether you see this solely-human or ‘that of God’ within us, surely being in contact with the wonder of this is an important, a spiritual experience?

Harrowed, hallowed. I guess that’s the Caravaggio rubber I’m taking home, clutched tightly and precious in my grubby human hand.

*For another account of how art connects us with the bare bones of being human, see ‘Musee des Beaux Arts‘.