As we all know, Her Royal Perkiness Queen Julie reaches for her favourite things when the dog bites, when the bee stings, and when she’s feeling sad.

As we all know, Her Royal Perkiness Queen Julie reaches for her favourite things when the dog bites, when the bee stings, and when she’s feeling sad.

Bee-wise, I’ve been fine. But I did get nipped by a dog the other week—one of those tiny jobs, all hair and needle teeth, about 5 inches tall and clearly feeling it had a lot to prove—and generally there’s been a lot of hard stuff going on recently: people I love getting more poorly, scarily so; a family funeral, and sorting a dead relative’s stuff; and—less dramatically but also hitting the yes, we’re all mortal spot—an injury I’ve had for over a year now which has knackered my sleep, been increasingly painful, prevented me doing all sorts of things and, simply, got me down. So I was in need of some favourite things. Cue thing 36: Hardy meets Schubert, courtesy of the Wordsworth Trust.

For a few years now the WT has been doing an annual music ‘n’ poetry ‘n’ supper evening at a veggie guest house in Cumbria. Not deepest Cumbria, but fairly deep—down a windy lane off a windy lane off a windy B-road which leads between Ambleside and Coniston. On this early spring evening the sky was full of cloud, the daffs were out, and the woods were in that lovely expectant state of just thinking about getting green again. It wasn’t dark yet but the light was draining from the sky, and I was glad to find my way safely to the guesthouse and find a parking spot right outside the front door. My friend Glenn was there already, and together we went up the steep steps and into the house.

I’ve only ever been to the Yewfield for the two supper recitals I’ve been to, so my sense of it is inevitably coloured by that. In my mind, then, it’s dimly lit and, well, brown, and being there feels like stepping into a sepia, slightly dog-eared, stiffly-posed photograph. Each time—I’m trying to be fair, here, and fully accept that daylit it may feel entirely different—I’ve felt that there’s something slightly out of time about it, in a way which is neither endearing nor unendearing, but not quite relaxing either. It’s not creepy or shabby, just… slightly odd.

My sense of the place won’t be helped, of course, by the old-fashioned nature of the event: with poetry reading, piano playing and a light supper around 9pm it was a sort of C19th, after-dinner-in-the-withdrawing-room experience, senza hooped frocks and discreet flirtations (or at least no-one was flirting with me). In addition, the Friends of the Wordsworth Trust are not exactly a banging crew; so that this evening, as last year, Glenn’s and my presence lowered the average age of the audience by about 20 years (and jings, I’m 51!). I felt ectopic and in need of a glass of wine, but I was going to have to wait till half time for that. We managed to get seats which allowed us a view of the business end of the piano—a splendid Steinway grand, lid open and set centre stage in the heavily-swagged bay window. The readers took their places at the lecturn and the night’s entertainment kicked off.

My sense of the place won’t be helped, of course, by the old-fashioned nature of the event: with poetry reading, piano playing and a light supper around 9pm it was a sort of C19th, after-dinner-in-the-withdrawing-room experience, senza hooped frocks and discreet flirtations (or at least no-one was flirting with me). In addition, the Friends of the Wordsworth Trust are not exactly a banging crew; so that this evening, as last year, Glenn’s and my presence lowered the average age of the audience by about 20 years (and jings, I’m 51!). I felt ectopic and in need of a glass of wine, but I was going to have to wait till half time for that. We managed to get seats which allowed us a view of the business end of the piano—a splendid Steinway grand, lid open and set centre stage in the heavily-swagged bay window. The readers took their places at the lecturn and the night’s entertainment kicked off.

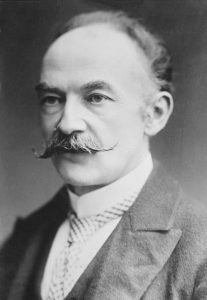

Schubert’s music alternated with readings of Hardy’s poems, early and late, the whole tacked together with a well-judged narrative of his life which gave a sense of the man without getting too bogged down in detail. I’d written on Hardy about a thousand years ago, as part of my PhD, but that had featured more prose than poetry so it was good to hear poems I wasn’t familiar with as well as being reminded of lines I’d pored over so much, so long ago. As we’d taken our seats I’d said to Glenn, ‘Here comes an evening about things which might have happened but didn’t, or happened once but happen no longer,’ and, though I hold by that as a fair if casual description of the general vibe of his poetry, it sounds more dismissive than I feel about his writing. I love the apparent simplicity, the commitment to the forms and spirit of lyric poetry, the unabashed owning of his melancholy and struggles, and the way he worries away at ideas of time, eternity and the painful brevity of human life. The evening’s narrative emphasised the loneliness he experienced as an atheist at that time and I found myself wondering how many others were comforted by the openness with which he expressed this.

Schubert’s music alternated with readings of Hardy’s poems, early and late, the whole tacked together with a well-judged narrative of his life which gave a sense of the man without getting too bogged down in detail. I’d written on Hardy about a thousand years ago, as part of my PhD, but that had featured more prose than poetry so it was good to hear poems I wasn’t familiar with as well as being reminded of lines I’d pored over so much, so long ago. As we’d taken our seats I’d said to Glenn, ‘Here comes an evening about things which might have happened but didn’t, or happened once but happen no longer,’ and, though I hold by that as a fair if casual description of the general vibe of his poetry, it sounds more dismissive than I feel about his writing. I love the apparent simplicity, the commitment to the forms and spirit of lyric poetry, the unabashed owning of his melancholy and struggles, and the way he worries away at ideas of time, eternity and the painful brevity of human life. The evening’s narrative emphasised the loneliness he experienced as an atheist at that time and I found myself wondering how many others were comforted by the openness with which he expressed this.

Lovely as it was to be read to, on this particular evening I found it even lovelier to be played to. Piano and cello are the instruments I most delight in hearing, and though for me Bach will always claim the first few spaces in my personal top 50, it has to include the Impromptus, too; so I was delighted to find that some were featured tonight. As the pianist began playing one, instinctively I closed my eyes—I can surrender to music and poetry (and probably most things) more thoroughly if I exclude sight—but then thought ‘How often is the piano playing live, right here in front of you?’, and opened them again. Watching the wondrous, unflashy dexterity of the pianist’s fingers I longed to be transported by the music, but was distracted by the creaking of the piano stool as he moved and the EXTREMELY irritating way that a grandly-dressed white haired woman two seats over from me was wriggling her feet almost incessantly, causing her patent, black leather, sensible-heeled loafers to squeak against each other (and this continued, approx. every 7 seconds, THROUGHOUT the evening). Good thing we’d had to check in our weapons at the door.

Lovely as it was to be read to, on this particular evening I found it even lovelier to be played to. Piano and cello are the instruments I most delight in hearing, and though for me Bach will always claim the first few spaces in my personal top 50, it has to include the Impromptus, too; so I was delighted to find that some were featured tonight. As the pianist began playing one, instinctively I closed my eyes—I can surrender to music and poetry (and probably most things) more thoroughly if I exclude sight—but then thought ‘How often is the piano playing live, right here in front of you?’, and opened them again. Watching the wondrous, unflashy dexterity of the pianist’s fingers I longed to be transported by the music, but was distracted by the creaking of the piano stool as he moved and the EXTREMELY irritating way that a grandly-dressed white haired woman two seats over from me was wriggling her feet almost incessantly, causing her patent, black leather, sensible-heeled loafers to squeak against each other (and this continued, approx. every 7 seconds, THROUGHOUT the evening). Good thing we’d had to check in our weapons at the door.

But as I became able to focus I suddenly had one of those strange moments—as when, on old radios, you twirled the dial and suddenly found yourself right in the sweet spot where the sound settles and clarifies absolutely—and I could feel, rather than just know intellectually, that I was going to die. Not imminently, you understand—but that my mortality is a fact. I felt the strange, terrible, anguished sweetness of it. I say sweetness because, so swiftly after that sense of death that it felt simultaneous with it, came the twin sense of being utterly, entirely alive. I felt fully in, fully possessed of, this moment of peace and beauty; and in that dimly-lit room full of strangers, where air itself was made exquisite with sound, I wept (suitably discreet) tears in which grief and gratitude were blended, indistinguishable.

Supper, wine and more poetry and music followed; and by ten-ish we were all rising from our seats and wrapping up again to go out into the night air. Last year, when we emerged, Glenn stopped me in the car park, saying softly, ‘Look’, and pointing up at the sky, which was brilliant with the most extraordinary yellow-bright stars. The sky felt so near to us, so soft and lovely and large. This evening, because of the cloud, that final gift was missing.

Supper, wine and more poetry and music followed; and by ten-ish we were all rising from our seats and wrapping up again to go out into the night air. Last year, when we emerged, Glenn stopped me in the car park, saying softly, ‘Look’, and pointing up at the sky, which was brilliant with the most extraordinary yellow-bright stars. The sky felt so near to us, so soft and lovely and large. This evening, because of the cloud, that final gift was missing.

But hey. There can’t always be stars.

You can read the poem from which the post’s title comes here. And you can have yourself a Schubert treat here or here.

Thank you Lucy, for sharing so much.

If it speaks, then I’m delighted x

This is absolutely beautiful

Thank you, Simon. As I said to Meg, if it speaks to you, then my work is done x

Made me cry -again- Lucy! I’m very partial to Hardy’s poetry, although I know he’s not fashionable, but I didn’t know that one. And I heartily sympathise with the distracting noise irritation – I try so hard to be charitable, but mostly fail!! (Glad to see Simon liked it too…. )