I’m usually a slow getter-inner, when lake or river swimming in Britain.

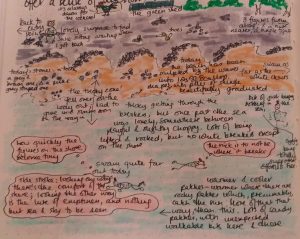

I enjoy the gradual acclimatisation process, and the way I eventually reach a point where postponing the gasp-inducing full plunge becomes worse than enduring it. On this beach, however, you have to let go of any vision of strolling casually or lingeringly across white-gold sand into lapping clear blue water as your footprints dissolve beautifully behind you. This is a stagger and flounder job: the stones, pebbles and shingle are hot beneath the soles of my feet, and really quite uncomfortable, rising to painful at times. They also shift as they take my weight, so that I slide and slip and occasionally lurch. I remember an advert years ago, which featured a lizard on hot sand, lifting opposite feet alternately while the voiceover said ‘Hot. Hot. Hot hot hot hot hot…’ I remind myself of that lizard.

I enjoy the gradual acclimatisation process, and the way I eventually reach a point where postponing the gasp-inducing full plunge becomes worse than enduring it. On this beach, however, you have to let go of any vision of strolling casually or lingeringly across white-gold sand into lapping clear blue water as your footprints dissolve beautifully behind you. This is a stagger and flounder job: the stones, pebbles and shingle are hot beneath the soles of my feet, and really quite uncomfortable, rising to painful at times. They also shift as they take my weight, so that I slide and slip and occasionally lurch. I remember an advert years ago, which featured a lizard on hot sand, lifting opposite feet alternately while the voiceover said ‘Hot. Hot. Hot hot hot hot hot…’ I remind myself of that lizard.

On the gentler days there’s a stretch of about 6 feet of of largeish rocks and pebbles underwater, just after the very fine shingle at the water’s edge.  Lurching and slipping is less worrying here because the water will catch me. And that’s part of what I love about wild swimming: being held in the safe arms of the water. Here I can simply fall forward into the womb-warm salt-silky sea―exactly the green-blue/blue-green colour of one of my favourite Crayola wax crayons when I was a child―and I am received, and rocked, and lilted. I laugh with sheer delight.*

Lurching and slipping is less worrying here because the water will catch me. And that’s part of what I love about wild swimming: being held in the safe arms of the water. Here I can simply fall forward into the womb-warm salt-silky sea―exactly the green-blue/blue-green colour of one of my favourite Crayola wax crayons when I was a child―and I am received, and rocked, and lilted. I laugh with sheer delight.*

Some days I swim straight out, some days along. On the along days I sometimes aim to swim as far as certain objects on the shore―and I notice what a time it can take to reach them, when they’d seemed only minutes’ away. The flip side of being supported is that there’s more resistance from the medium. But it’s also probably true that it’s simply difficult to tell quite how far I am going, when I am swimming far out―hard to see what I’m achieving.

The sea bottom is mostly sand once I’m a way out. It’s sculpted into rippling Borrowers’ mountains and valleys which are batiked with dancing lines of refracted light.  They’re delicious underfoot, moulding to the contours of my toes (though I guiltily imagine the Sea-Borrower population swimming frantically for safety as their environment is destroyed). There are also rocky bits, where the water darkens and slithery weed-fingers reach up for me. That always makes me quicken my stroke; though when I’m snorkelling, and can see what I’m swimming over, I’m not creeped out at all.

They’re delicious underfoot, moulding to the contours of my toes (though I guiltily imagine the Sea-Borrower population swimming frantically for safety as their environment is destroyed). There are also rocky bits, where the water darkens and slithery weed-fingers reach up for me. That always makes me quicken my stroke; though when I’m snorkelling, and can see what I’m swimming over, I’m not creeped out at all.

On days when the water is more active, it takes quite a lot of effort to get over the rocky stretch on entry, because the waves, getting into their stride, are enthusiastically filling themselves full of shingle and small stones, and flinging them at the beach and anyone attempting to enter the water. This can get painful, but the risen water is wonderful once you get through the initial pain barrier; and to be played with and lifted by the rolling water is sheer pleasure.

On days when the water is more active, it takes quite a lot of effort to get over the rocky stretch on entry, because the waves, getting into their stride, are enthusiastically filling themselves full of shingle and small stones, and flinging them at the beach and anyone attempting to enter the water. This can get painful, but the risen water is wonderful once you get through the initial pain barrier; and to be played with and lifted by the rolling water is sheer pleasure.  I caught myself thinking the trick is not to be where it breaks; and this seemed ludicrously symbolic of some kind of cosmic life-truth, as well as a fact about the sea. On other days it’s simply too wild, and it’s time to abandon the attempt, gracefully. (Ditto.)

I caught myself thinking the trick is not to be where it breaks; and this seemed ludicrously symbolic of some kind of cosmic life-truth, as well as a fact about the sea. On other days it’s simply too wild, and it’s time to abandon the attempt, gracefully. (Ditto.)

Every day when I go down there, I see three figures far down along the shore They’re usually already swimming when I arrive—a man and two children, young I’d say, under 8. I swim along past them, but much further out, so that their heads are just bobbing dots in the distance. It astonishes me each time quite how quickly figures in the shallows or on the shore diminish in size: they’re so tiny, smaller than my held-up hand. And yet it is still obvious that the man is middle-aged, at least: you can see, even from here, the effects of time and gravity on the form, how years and experience are registered in the flesh.

On another, more populated beach the other day, I was watching an early-teenage girl get ready to swim. The flesh was sparse on her Bambi-bones; her skin was unblemished, collagen-plump, perfect; and her shoulder blades jutted and moved under it like just-about-to-sprout wings. Her mum came in from the sea as she was going in, and I could see the dimpled, heavy thighs, the time-sagged breasts, the thickened waist. But what I was struck by was that these were simply different beauties: one unused, unmarked, a body not really lived in much, yet; one shaped by experience, inhabited—a body lived in, hard-working, rich in its years. ‘Beauty is not the same thing as youth’, says Neil Hannon in ‘Note to Self’. Our culture struggles to remember this fact, and that is so sad.

I am held, bobbing, in this delicious water, which shares, for this moment, the task of bearing my own fifty-years’-used body. I have a glorious sense of being fully in touch with that body, fully inside it.

And every inch of it sings.

*see ‘sea-glass‘