“It’s a high-risk activity,” the doctor I’d never met told me, down the phone. The man was a stranger and here I was having to talk to him about cramps and diarrhoea so that he could pronounce sagely about the potential for me shitting myself in a field. That’s a possibility? You don’t say.

“It’s a high-risk activity,” the doctor I’d never met told me, down the phone. The man was a stranger and here I was having to talk to him about cramps and diarrhoea so that he could pronounce sagely about the potential for me shitting myself in a field. That’s a possibility? You don’t say.

But St Hilda’s Way had been beckoning for months. We’d booked hotel rooms, consulted local bus timetables, contemplated sawing handles off toothbrushes so as to be carrying less weight and obsessively checked weather forecasts in the hope that predicted thunderstorms would somehow not materialise. There was no way I was missing this. My guts were just going to have to—well, get their shit together. I got St Loperamide on side, as well as Hilda, and hoped for the best.

The SHW starts in Hinderwell, which is a bit up from Whitby (you can see how honed my nav skills are) where we were leaving the car and getting a bus up the coast. We’d both have preferred to use public transport but the train journey is one of those cross-country epics which involves about 5 changes and takes a scarcely believable 6-7 hours. Depressing, in various ways. However. After 24 hours’ or so of texting to and fro—waterproof trousers? one pair of socks or two? book or no book?—Jenny and I met and weighed our packs, finding mine was a lot heavier but then remembering that it currently contained my boots. Notebook, purse, phone. Time to go. I was tired and distracted and struggling to follow through on the simplest of tasks. Rucksacks in the boot. “Don’t you need your phone for the micro-nav in Whitby?” Oh yes. Phone out of pack, and water bottle. Go to close boot. “Your phone, Lucy.” Phone now lost in boot. Empty boot. Refill boot. Shake rucksack. Clatter of phone falling from wherever it had hidden itself. Great! Go to close boot. “No, your phone, Lucy.” Oh yes, again. Finally have phone in one hand and water in the other. Not enough hands or shoulder mobility to close boot. Jenny obliged, and at last we were off.

The SHW starts in Hinderwell, which is a bit up from Whitby (you can see how honed my nav skills are) where we were leaving the car and getting a bus up the coast. We’d both have preferred to use public transport but the train journey is one of those cross-country epics which involves about 5 changes and takes a scarcely believable 6-7 hours. Depressing, in various ways. However. After 24 hours’ or so of texting to and fro—waterproof trousers? one pair of socks or two? book or no book?—Jenny and I met and weighed our packs, finding mine was a lot heavier but then remembering that it currently contained my boots. Notebook, purse, phone. Time to go. I was tired and distracted and struggling to follow through on the simplest of tasks. Rucksacks in the boot. “Don’t you need your phone for the micro-nav in Whitby?” Oh yes. Phone out of pack, and water bottle. Go to close boot. “Your phone, Lucy.” Phone now lost in boot. Empty boot. Refill boot. Shake rucksack. Clatter of phone falling from wherever it had hidden itself. Great! Go to close boot. “No, your phone, Lucy.” Oh yes, again. Finally have phone in one hand and water in the other. Not enough hands or shoulder mobility to close boot. Jenny obliged, and at last we were off.

After an initial bit of nav uncertainty we were trundling across country, stuck behind camper vans and aggregate lorries from time to time, but on the whole feeling quite mellow about the journey. I wondered why Google directions always name the roundabouts—who can tell if they’re going round the Cynthia Forsythe/Robin Lightwood/whoever roundabout?—while Jenny had an even deeper question: “What is Teesside?” “A state of mind,” I replied.

Once we were off the A1 and heading east we started passing beautiful hamlets and villages of honey-coloured stone. Soon we had our first sighting of the sea. There was a spectacular entry to the coast road from the north at Sandsend: stretching before us were long scallops of golden beach which were being lapped by gentle, abroad-blue waves frilled with the smallest, most decorative of white horses. In the distance was Whitby, the Abbey ruins rising on the cliffs behind. What with fishing nets on bamboo sticks and toddlers with buckets and lobster-coloured injudiciously dressed parents, there was a timeless British Seaside Holiday vibe going on. Lovely.

Whitby itself was busy and overwhelming, but Jenny had thoroughly researched The Parking Situation (notorious, apparently) and beetled into the Tourist Info to buy us a permit while I loitered, preparing to speak French to any approaching wardens. Permitted, we snagged the last available place in a central long-stay car park and, stiff-hipped from sitting, I got Lurchily out of the car. We had time to have a cup of tea so, enjoying the last moments of not carrying everything we needed on our backs, we strolled past the Endeavour, round the river’s edge. Squealing people were hauling up crabs in buckets, which was horrible to see; a poster advertised shark-fishing trips, which seemed unlikely; and everywhere gulls were shitting (I could relate) and mewing and waiting for their chance to grab any dropped chips.

Whitby itself was busy and overwhelming, but Jenny had thoroughly researched The Parking Situation (notorious, apparently) and beetled into the Tourist Info to buy us a permit while I loitered, preparing to speak French to any approaching wardens. Permitted, we snagged the last available place in a central long-stay car park and, stiff-hipped from sitting, I got Lurchily out of the car. We had time to have a cup of tea so, enjoying the last moments of not carrying everything we needed on our backs, we strolled past the Endeavour, round the river’s edge. Squealing people were hauling up crabs in buckets, which was horrible to see; a poster advertised shark-fishing trips, which seemed unlikely; and everywhere gulls were shitting (I could relate) and mewing and waiting for their chance to grab any dropped chips.  We had tea in the charmingly old-fashioned Bothams High Class Café; my Earl Grey came in a splendid hand-tied reusable muslin bag, and was absolutely delicious.

We had tea in the charmingly old-fashioned Bothams High Class Café; my Earl Grey came in a splendid hand-tied reusable muslin bag, and was absolutely delicious.

Then it was back to the car, and packs on. The bus station was only a few moments’ walk from the car park but as I swung my pilgrim’s staff and took those first paces I was filled with elation. That delicious sense of possibility, of being at the start of things, of something unknown and full of potential stretching out before us: everything still to come. The unwritten page. Glorious.* Just at that moment I noticed a café sign advertising ‘Chips and glories’. Who knew there were so many kinds?

The X4 pulled up early and the kind bus driver agreed to let us know when we got to Staithes, “though,” he added darkly, “She tells you”. It turned out to be a talking bus. She had a lot to say. Not driving, I was now able to notice more details of what we passed through and was particularly pleased to see a floral clock on a grassy bank at the side of a park. Took me back years. It was a proper rural bus ride, too, winding in and out of villages, doubling back on itself and dropping tired, end-of-the-working-day locals off at isolated bus stops. All this novelty was their everyday; one of those things I’m often reminded of when I’m being a tourist.

At Staithes we found Captain Cook’s Inn, where we were to spend the night before the walk. Even this early in the trip, here was a landmark experience: my first ever time of opening my hotel room door and not being disappointed. There’s usually something which feels like a let down, even if I’d struggle to say exactly what; but this was a clean, spacious, double-bedded room, with a good stash of sachets and a useful array of bathroom stuff. There was somewhere for me to sit and write, and even a fan to deal with the night time flushes. The bathroom had a large, square, pleasingly old-fashioned and solid but sparklingly clean basin, and a shower in which there was actually room to turn round. I used some of the supplied shower gel to ‘revitalise’ my pants for the next day (I later discovered Jenny had made the same choice) and then enjoyed a drink and a bask in the large armchair in the bay window in Jenny’s room. Her room was even nicer—flooded with sunlight and looking out over fields to the coast—but by what Clive James calls “the kind of bloodless compromise possible only between adults” we’d agreed to take it in turns to have the better room.

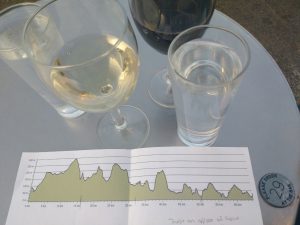

As we walked down towards the harbour and centre of the village, I had a sudden visual memory of some childhood summer spent in Cornwall. Though I’d never been to Staithes before, this all felt so familiar: the narrow, windy, cobbled streets lined with cottages—some painted in Neapolitan ice cream seaside-y colours—and descending so steeply to the sea… I’ve no idea what holiday I was recalling, but there was something lovely about the way the memory surfaced, unbidden. At the Cod and Lobster we had a pricey but ok dinner, and looked at the sea, the cliffs, and The Documents about the next day’s walk. My inner Anorak loved it that Jenny had printed out a graph of the ascent/descent over the next four days;

As we walked down towards the harbour and centre of the village, I had a sudden visual memory of some childhood summer spent in Cornwall. Though I’d never been to Staithes before, this all felt so familiar: the narrow, windy, cobbled streets lined with cottages—some painted in Neapolitan ice cream seaside-y colours—and descending so steeply to the sea… I’ve no idea what holiday I was recalling, but there was something lovely about the way the memory surfaced, unbidden. At the Cod and Lobster we had a pricey but ok dinner, and looked at the sea, the cliffs, and The Documents about the next day’s walk. My inner Anorak loved it that Jenny had printed out a graph of the ascent/descent over the next four days;  like I said, this woman is thorough with her planning. It looked alarming till I realised that the highest point was only about the same as Loughrigg Fell: there was going to be nothing like the St Bega’s Way epic last year, although the distances were greater. I was relieved. In the year since the SBW I still hadn’t managed to replace those bloody boots which ate my feet. I hoped that less up-and-downing might help avoid that this time.

like I said, this woman is thorough with her planning. It looked alarming till I realised that the highest point was only about the same as Loughrigg Fell: there was going to be nothing like the St Bega’s Way epic last year, although the distances were greater. I was relieved. In the year since the SBW I still hadn’t managed to replace those bloody boots which ate my feet. I hoped that less up-and-downing might help avoid that this time.

The following morning we had to breakfast with Boris Johnson—how I loathe the ubiquity of screens in shared spaces—but soon got booted and rucksacked and set out into the bright sun and pleasant breeze. We’d decided to go the long way round to Hinderwell, and passed the shop and café we’d admired yesterday before turning on to the path to the headland, where we were rewarded with a wide blue sky, the glittering stretch of the sea,

The following morning we had to breakfast with Boris Johnson—how I loathe the ubiquity of screens in shared spaces—but soon got booted and rucksacked and set out into the bright sun and pleasant breeze. We’d decided to go the long way round to Hinderwell, and passed the shop and café we’d admired yesterday before turning on to the path to the headland, where we were rewarded with a wide blue sky, the glittering stretch of the sea, and beautiful views down the coast. After twenty minutes, maybe, we said farewell to the sea till Friday and went right, down a metalled road into Hinderwell itself, arriving at St Hilda’s church, which is built at a place where she and her companions stopped some 1500 years ago. They’d been on the way to Whitby and were in need of refreshment. Hilda herself is reputed to have discovered the spring which rises, still, in the churchyard.

and beautiful views down the coast. After twenty minutes, maybe, we said farewell to the sea till Friday and went right, down a metalled road into Hinderwell itself, arriving at St Hilda’s church, which is built at a place where she and her companions stopped some 1500 years ago. They’d been on the way to Whitby and were in need of refreshment. Hilda herself is reputed to have discovered the spring which rises, still, in the churchyard.

This was it, then. This was where our SHW really began.

*More about beginnings… I couldn’t choose between two very different poems, so see what you make of them both, here and here.

Hope the guts settled!

Looking forward to the next bit, as you probably walked very near to the farm in Glaisdale where I lived, and through Lealholm where I went to my first school!

Yes, we went to/through both those places. Read on! x