If we’d packed sun cream, of course, it would have peed down all week. As it was we only had my calculated-for-weight modicum of SPF moisturiser and it looked like there’d be sun, on and off, for the next two days. Fortunately, Danby Health Shop was right next door to the Duke. Inside, we breathed deeply of that arcane herbs smell proper to independent healthfood shops. Jenny invested a quietly startling amount of money in some extremely wholemeal organic sun cream, and we went outside to get ‘slapped up’, as Susie and I call it.

If we’d packed sun cream, of course, it would have peed down all week. As it was we only had my calculated-for-weight modicum of SPF moisturiser and it looked like there’d be sun, on and off, for the next two days. Fortunately, Danby Health Shop was right next door to the Duke. Inside, we breathed deeply of that arcane herbs smell proper to independent healthfood shops. Jenny invested a quietly startling amount of money in some extremely wholemeal organic sun cream, and we went outside to get ‘slapped up’, as Susie and I call it.

Easier said than done. The texture of the cream was such that, even after a good few minutes’ rubbing, we still looked like we’d been prepped to swim the channel. Better than getting lobstered, though. We slithered our way into our packs and set off on the ‘Danby Loop’ section of the SHW.

St Hilda’s Church at Danby is some way out of the village, and we strode down quiet roads, chatting, reviewing breakfast (not much provision for veggies) and coming to terms, again, with the weight of our rucksacks. As we rounded a bend, I spotted a critter at the edge of the road ahead of us— weasel? stoat? not sure—but didn’t get the words out in time to alert Jenny. We agreed on a slightly military sounding “Mustelid: one o’clock!” system for future use.* Round a further bend another mustelid was at ten o’clock, frozen for a moment, watching us from the base of the bushy hedgerow before undulating its way back into the lush green depths. We were seeing a lot of dead things on this walk—including a young, rankly ripe red deer at the base of a tree in a wood, its legs crumpled and pointing up the trunk in a strange and rather pathetic manner—so it was good to see living things too.

weasel? stoat? not sure—but didn’t get the words out in time to alert Jenny. We agreed on a slightly military sounding “Mustelid: one o’clock!” system for future use.* Round a further bend another mustelid was at ten o’clock, frozen for a moment, watching us from the base of the bushy hedgerow before undulating its way back into the lush green depths. We were seeing a lot of dead things on this walk—including a young, rankly ripe red deer at the base of a tree in a wood, its legs crumpled and pointing up the trunk in a strange and rather pathetic manner—so it was good to see living things too.

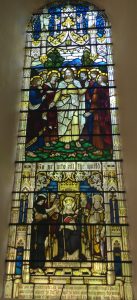

The church felt like a living thing as well. We looked at the Missionary window, and my inner Lambhunter particularly admired the detail in the ‘Good Shepherd’ window; the artist had the baggy wrinkliness of the lamb’s skin just right. I sat for some moments in the vital quiet—silent, connecting with myself and the griefs I was bringing on the pilgrimage with me. I felt how they were a part of everything, just like the joys, and had the relief of tears.

The church felt like a living thing as well. We looked at the Missionary window, and my inner Lambhunter particularly admired the detail in the ‘Good Shepherd’ window; the artist had the baggy wrinkliness of the lamb’s skin just right. I sat for some moments in the vital quiet—silent, connecting with myself and the griefs I was bringing on the pilgrimage with me. I felt how they were a part of everything, just like the joys, and had the relief of tears.

Then it was back out across the moor side, where there was more evidence of quite how good they are at bracken in this part of the world. Jenny told me that, strictly speaking, any given extent of bracken should be understood as one plant, connected as it is by the rhizomes which network the earth beneath. This all felt a bit John Wyndham and creepy to me, particularly when the track was barely discernible, the greenery as high as my head, and some sheep came barrelling noisily out of it at twelve o’clock, both startled and startling. Under a dappled sky of grey and blue we fought our way towards Low Coombs farm, over a ladder stile, and along the edge of some fields where a hairy-topped, light gold crop was still in the windless air.

Suddenly we were in the car park at the Moors Visitor Centre. Cars people noise. No thanks. Unconsciously speeding up, we followed the Esk Valley Walk leaping salmon blazes along the road and left across a ridged-and-furrowed field. Here the cags went on briefly, before coming off again during a short, stiffish climb up behind a farm to join Lodge Lane. I stopped to take a photo, fumbled with and dropped my phone, and discovered when I picked it up that a stone had made a small, neat hole in the screen. Bollocks.

Suddenly we were in the car park at the Moors Visitor Centre. Cars people noise. No thanks. Unconsciously speeding up, we followed the Esk Valley Walk leaping salmon blazes along the road and left across a ridged-and-furrowed field. Here the cags went on briefly, before coming off again during a short, stiffish climb up behind a farm to join Lodge Lane. I stopped to take a photo, fumbled with and dropped my phone, and discovered when I picked it up that a stone had made a small, neat hole in the screen. Bollocks.

But also, I noticed, not bollocks. I didn’t actually care, beyond the nuisance of having to replace it. I felt pleased to discover how unattached I was to the phone (though I recognise that ripping a favourite notebook might have been a whole different matter). This thought led me to another thought I’d already had several times during the walk: how pleasing it was to have so few choices. What do I do? Walk. What do I wear? The shorts and t-shirt in the day, the dress in the evening. What do I eat? What is available. What else is there to decide? Nowt. It was so refreshing. I was reminded of the decluttering I did at the turn of the year: that minimalism isn’t about owning only 37 things and painting the house white but rather about reducing choices and thus freeing your time and attention for what really matters.

To our left the moor stretched out the purple of heather and the brown-black of peat; the green patchwork of the Esk valley fell away to our right. A family of mountain bikers passed us, not one of them responding to our cheery greetings or even sparing us a glance. I’m so used to the easy fellside camaraderie you get in the Lakes that I was a bit disgruntled, being reminded of how on walks in Manchester I have to rein in my natural impulse to say hello. (It’s not quite as uncool as smiling at someone on the Tube, but it’s getting there.)

To our left the moor stretched out the purple of heather and the brown-black of peat; the green patchwork of the Esk valley fell away to our right. A family of mountain bikers passed us, not one of them responding to our cheery greetings or even sparing us a glance. I’m so used to the easy fellside camaraderie you get in the Lakes that I was a bit disgruntled, being reminded of how on walks in Manchester I have to rein in my natural impulse to say hello. (It’s not quite as uncool as smiling at someone on the Tube, but it’s getting there.)  We dined at the edge of the track, the glory of the valley spread before us, and I decided to hold off on eating my caramel wafer in case our teashop-with-cake fantasies about Lealholm, our next village, weren’t fulfilled. But after the steep descent down the flagged path at the roadside I exclaimed with joy—perhaps just a little too loudly—to see the sign for the Beck View Tea Rooms (other teashops were available). It even had the exact cakes we’d been dreaming about: result! We sat in the sun, enjoying the Beck View and slapping ourselves up again for the next leg. I looked at Jenny’s red-with-thick-white-smears face, knowing mine was the same. We could have been auditioning for Madame Butterfly.

We dined at the edge of the track, the glory of the valley spread before us, and I decided to hold off on eating my caramel wafer in case our teashop-with-cake fantasies about Lealholm, our next village, weren’t fulfilled. But after the steep descent down the flagged path at the roadside I exclaimed with joy—perhaps just a little too loudly—to see the sign for the Beck View Tea Rooms (other teashops were available). It even had the exact cakes we’d been dreaming about: result! We sat in the sun, enjoying the Beck View and slapping ourselves up again for the next leg. I looked at Jenny’s red-with-thick-white-smears face, knowing mine was the same. We could have been auditioning for Madame Butterfly.

Pressing on in the direction of Glaisdale we passed through Underpark farm, where we delighted in some deliciously Disney new calves, all clean and wobbly and lushly long-lashed. Young chickens shot about the yard, overseen by a rooster so gloriously bouffant and dishevelled that he could have been drawn by Dr Seuss after one too many coffees. During a section along the riverside we noticed how strangely dull and murky the water was, with a curious reddish-brown colour. Even in full sun it didn’t glint. Had it been stirred up by recent rains, or was there something more sinister going on? Odd.

Pressing on in the direction of Glaisdale we passed through Underpark farm, where we delighted in some deliciously Disney new calves, all clean and wobbly and lushly long-lashed. Young chickens shot about the yard, overseen by a rooster so gloriously bouffant and dishevelled that he could have been drawn by Dr Seuss after one too many coffees. During a section along the riverside we noticed how strangely dull and murky the water was, with a curious reddish-brown colour. Even in full sun it didn’t glint. Had it been stirred up by recent rains, or was there something more sinister going on? Odd.

After a very transgressive-feeling scuttle through someone’s garden—it was where the path led but it still felt deeply intrusive and wrong—we passed a converted mill whose friendly owner, working in the garden, confirmed that the water had indeed been stirred up by the rain. Good to know. I was swallowing a large lump of house envy as we walked up the slope to join the road which would take us down into Glaisdale; but it was sunny, journey’s end was in sight, and we had just the right degree of tiredness to make the prospect of taking off our packs and settling into our latest home from home an inviting prospect.

But the fulfilment of our cakeshop fantasies and the two nights of luck and luxury with Captain Cook and the good Duke had lulled us into complacency. The first glimpse of the Arncliffe Arms—large footie-type trophy on display behind giant screen in dirty window—and our hearts sank. This did not look like good news. And indeed it wasn’t. The proprietor might just as well have painted, below the establishment’s name, a subtitle saying “We don’t give a shit about how comfortable you are here, we just want your money”. I was dumb with incredulity as the pleasant young woman showed us the rooms. I mean, how could she think this was ok? Was she cringing with embarrassment inside or had some kind of necessary numbness set in for her? How could this possibly cost the same £50 per night as the last places?

The lock on Jenny’s door seemed to have been drilled out and replaced at some point. Outside her window some chuggy piece of machinery made generator noises in the scruffy car park (and did so all night). The fire door on the stairs was streaked with dirt—looked as though it had been kicked in at least once—and on the half-landing a pile of paint cans and assorted building bits-and-pieces sprawled on the tired looking carpet, together with a picture (of Ambleside, weirdly) propped up on its side. The bed-base in my room had dirty marks on it, the walls were grubby; there was nowhere to sit down. The window, once opened, flew out so wide that I couldn’t reach it to close it; and there was nothing to stand on, either, so open it stayed. My bedside table appeared to be a small set of filing drawers (Jenny’s was in front of the bedside light switch, so you couldn’t switch the light on without rearranging the furniture; but it turned out not to work anyway). Meanwhile in the dingy “bathrooms” my basin was cracked and the shower gel and soap were in screwed-to-the-wall don’t steal this dispensers; Jenny spent some time trying to pump gel out of hers before realising it was empty. Overhead the light-

The lock on Jenny’s door seemed to have been drilled out and replaced at some point. Outside her window some chuggy piece of machinery made generator noises in the scruffy car park (and did so all night). The fire door on the stairs was streaked with dirt—looked as though it had been kicked in at least once—and on the half-landing a pile of paint cans and assorted building bits-and-pieces sprawled on the tired looking carpet, together with a picture (of Ambleside, weirdly) propped up on its side. The bed-base in my room had dirty marks on it, the walls were grubby; there was nowhere to sit down. The window, once opened, flew out so wide that I couldn’t reach it to close it; and there was nothing to stand on, either, so open it stayed. My bedside table appeared to be a small set of filing drawers (Jenny’s was in front of the bedside light switch, so you couldn’t switch the light on without rearranging the furniture; but it turned out not to work anyway). Meanwhile in the dingy “bathrooms” my basin was cracked and the shower gel and soap were in screwed-to-the-wall don’t steal this dispensers; Jenny spent some time trying to pump gel out of hers before realising it was empty. Overhead the light- fitting was encrusted with dirt so thick that when the light finally roused itself into faint life it showed clear sets of fingerprints in the muck. I knew if I thought about things too closely I wouldn’t be able to sleep in this bed. Oh dear. I had that horrible I’ve been ripped off feeling.

fitting was encrusted with dirt so thick that when the light finally roused itself into faint life it showed clear sets of fingerprints in the muck. I knew if I thought about things too closely I wouldn’t be able to sleep in this bed. Oh dear. I had that horrible I’ve been ripped off feeling.

Having pooled our dismay Jenny and I decided to walk to Egton, a couple of miles distant, to find somewhere to eat. The AA’s proprietor wasn’t getting a penny more of our money! I turned off my phone which had been getting hotter and hotter (not being tech minded, I feared it was leaking radiation into me and my rucksack), slid my feet into my Fitflops (my toe appreciated the Lebensraum) and we sped-walked along the road, enjoying the golden evening light; enjoying, too, our shared low-level fulmination. There’s something strangely pleasing about a sense of justified outrage. At Egton’s Witching Post we got fed and watered and Lucy the go-the-extra-mile waitress arranged for the landlord to give us a lift ‘home’ after he’d finished playing cricket. How lovely is that?

Back at the AA I lay in bed in my clothes, noting how it was possible to be supine but at the same time utterly clenched and unrelaxed. It was going to be a long night. I was also aware, though, of how the Arncliffe Experience had already become an anecdote in my head, a part of a history I now shared with Jenny; and in this it was something I could welcome—feel grateful for. Without a family of my own, I’m putting together a patchwork of shared histories involving the friends, pastimes and places which are so precious to me. I guess that’s part of what wtak is about. It all means so much to me.

Besides, the AA’s ungenerosity was such a contrast to the kindness and plenty we were meeting elsewhere. Up, down, light, shade. All part of the deal.**

*Jenny introduced me to this family name for weasels, badgers, otters and others. I managed to retain it in my menopausal brain only by dint of imagining a stoat wearing an apron (blue and white checked, actually), making a batch of jam and collecting jars and lids to put it in. This Memory Palace thing really works.

**More about ups and downs here in the wtak anthology.

I wish I’d know you were going to Glaisdale, you will have walked right past my Uncle and Aunt’s house at the top of the village (a small converted barn looking out on a grassy triangle, not far above the village institute). My aunt Mary, one of the most extraordinary people I’ve ever met, died there about a fortnight after you passed through, at the age of 96. They used to have an “organic” farm up Glaisdale dale.

Oh Oliver, what a shame. Sounds like yet another remarkable member of your clan.

Hello from France! You must have walked the route from Lealholm to underpark along the way I trekked home from school in Lealholm to Hall Park farm. This would be from 1949 to 1954!

Gosh that’s quite a coincidence, Meg. Can that really be 65 years ago?? x